As an African woman I am very well aware that although appearances aren’t quite everything, they are nonetheless very important – especially when it comes to one’s hair. From an early age the salon (or, as we pronounce it in my dear country, the saloon) becomes an integral part of our lives. I remember countless afternoons spent sitting on a small wooden stool getting my hair cornrowed for school, held firmly between the hairdresser’s thighs as she skilfully wove my obstinate hair into intricate patterns snaking along my scalp. It always made me laugh when I would talk to my British friends and they would tell me that the salon was where they went to be pampered: as a child, I was convinced that only mysterious army soldiers in darkened rooms could carry out more intense torture than a Surulere hair stylist. But all the pain and tears would be forgotten as soon as the hairdresser released me from her iron grip and I could scamper to the mirror and admire my new ‘do: from two-step to patewo, I loved seeing how my look would transform from one week to the next.

I was never particularly inventive with my hairstyles – probably because of a fear of the side-eye my mother would deliver if I did anything too unconventional – but one detail about my salon experiences that sticks out in my mind is the posters on the wall, interspersed between adverts for relaxer crèmes, that customers could use as inspiration. Pattern upon pattern with names like FESTAC (a residential area of Lagos) and Skyscraper covered the paper, and I would stare at them, mesmerised by their gravity-defying power and a little sad at the relative simplicity of my hairstyle. Glamorous they were, but unfortunately a little too grown up for a girl still in primary school.

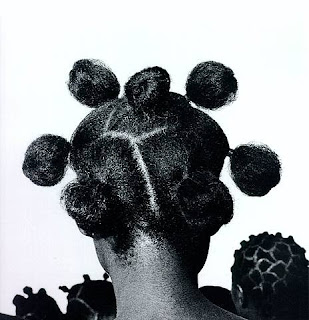

Years later, my nostalgia for those years and those posters was awoken by a feature on Next.com on the work of photographer J.D. Okhai Ojeikere. Along with his sons Iria and Amaize, Ojeikere has greatly influenced the direction of photography and documentation in Nigerian society, most famously through his 1960s series on urban hairdressers and the creativity with which they carved inspiring styles for women. His work provides a snapshot of a Nigeria that I never saw: a country recently freed of the burden of colonialism and full of hope and excitement for the future. Even though our history has forced some hard lessons on us, the remarkable spirit and beauty of his photographs reflect the resilience of Nigerians and the depth of our imaginations. And, as a Nigerian woman, they’re a wonderful reminder that my joy at the sight of a perfectly-coiffured head is shared by millions of my fellow citizens. Ojeikere’s photographs are stunning at first glance, but it is the careful thought and the countless stories behind them that make them so incredibly evocative and appealing.

No comments:

Post a Comment